I have always had a wander-bug. My wander-bug has taken me many places nationally and internationally. This time around my trip lead me to my motherland, my native place, Kutch. All my life, I had heard about it, but never seen it, but this was the time it really called up on me and I couldn’t resist the call.

Kutch is the largest district in the culture-rich state of Gujarat, covering a total area of 45,612 sq.km. Kutch gets its name from the Guajarati or Kutchhi word, Kacchbo or Kutchbo meaning tortoise. Probably the reason being that it is surrounded by water and housing some of the most exotic and rare marine life.

Being a seasoned traveler, I always prefer to do my homework well before traveling to any location like booking tickets and accommodation online, getting maps off the internet and information about places to see, etc. While doing this, I stumbled upon a website which informed me about an almost forgotten place known as Dholavira. It said, Dholavira houses one of the best preserved ruins maintained by the Archeological Survey of India dating back about 5000 years. Done, it struck a bell in my mind; I had to visit this place.

Even as of date, is situated 140 kms away from the nearest inhabitation, in spite of all the quakes, it stands witness to the achievement of man 5000 years back. Dholavira is located on an island of 200 acres, an island not surrounded by water, by abundance of highly saline marshes in the Great Rann of Kutch, a place where no man would ever conceive the idea of inhabitation. Where every drop of fresh water is considered at the price of gold and as far as your sight can see all you will get is bright dazzling salty mudflats as white as snow.

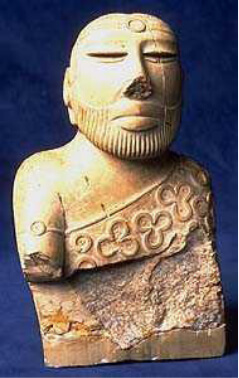

No points for guessing, these were The Harrappans. Yes, our own Indus valley civilization well preserved in India. You can now skip the hassle of visiting our friendly neighbors. The architecture, planning and archeological carbon analysis dates back to the Harappan period. In other words, it resembles Mohenjodaro and Harappa – it has a citadel middle and lower town, all extremely well preserved through being built in stone, Harappa and Mohenjo Daro being built in more vulnerable brick, which have pretty much crumbled.

The city probably could have been a stop-over for trade or even a fort protecting sea trade with Oman, Mesopotamia (a river civilization like the Indus Valley civilization, in present day Iraq), and the Persian Gulf and other far-off lands. Salt, of course could have been the commodity which they traded in, as informed by Mr. R.S.Bisht, the chief archeologist of this site. All that’s known is that these people worshipped the forces of nature like fire, wind, trees, etc.

They had proper entertainment facilities like playgrounds. And were ruled and organized by a ruler for whom the Citadel was built, and who enjoyed royalty stature.

The answer is “Water Management.

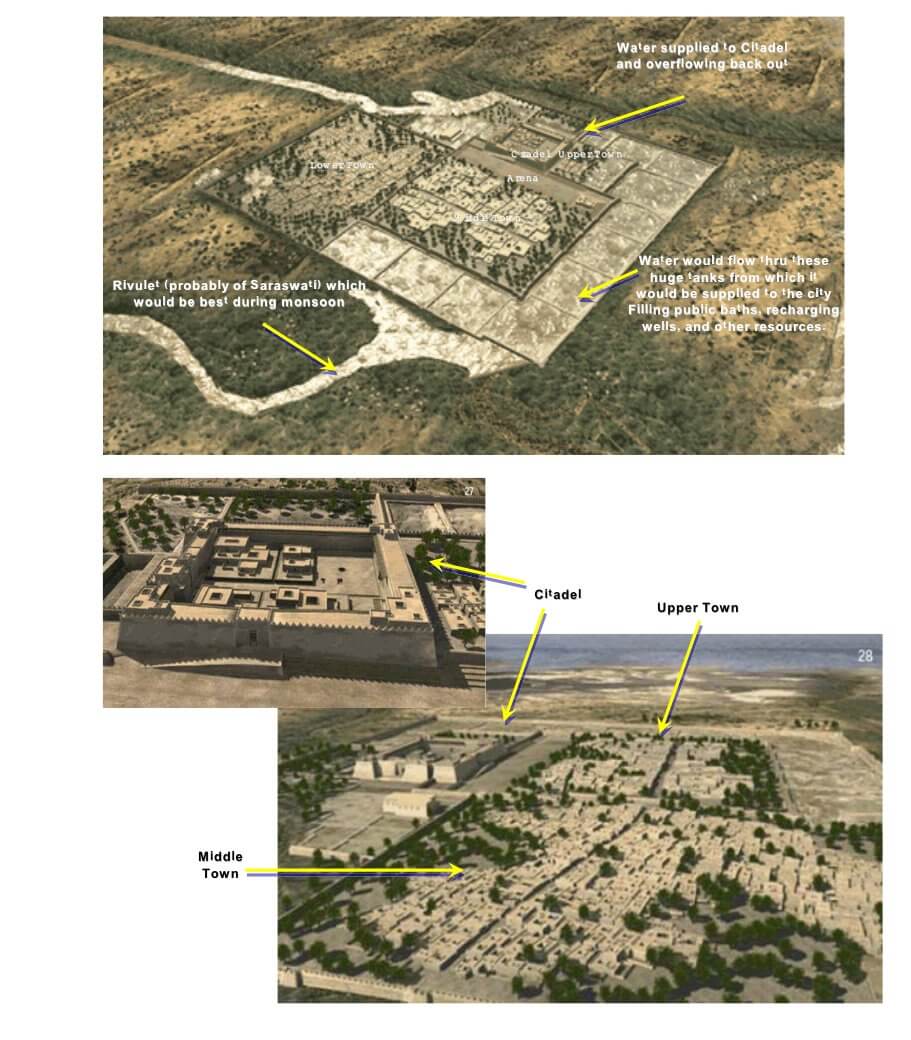

The city was built in a semi-arid region averaging only about 260 mm rainfall annually. Two storm water channels, known as Manhar and Mansar bordered the city. The city was laid out on about a 13 m gradient in the east-west direction, and of course a perfect planning for reservoirs. They made a series of around 16-18 reservoirs between the inner and outer walls of the city to collect the monsoon runoff from the channels.

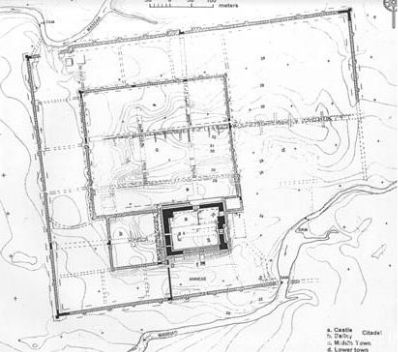

The town planning itself would put a modern township to shame. Segregated areas included the citadel of the ruler, the upper town for the loyal workers of the ruler, middle town and lower town, the occupants The city was built in a semi-arid region averaging only about 260 mm rainfall annually.

Two storm water channels, known as Manhar and Mansar bordered the city. The city was laid out on about a 13 m gradient in the east-west direction, and of course a perfect planning for reservoirs. They made a series of around 16-18 reservoirs between the inner and outer walls of the city to collect the monsoon runoff from the channels.

The town planning itself would put a modern township to shame. Segregated areas included the citadel of the ruler, the upper town for the loyal workers of the ruler, middle town and lower town, the occupants depending on their social and economic status. A huge playground arena for performing arts or sports, etc. A detailed image shows the planning.

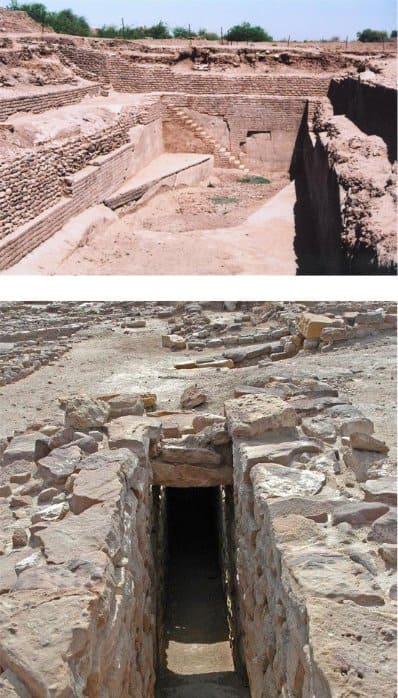

Here, we can see one of the reservoirs built for water storage. As one can see, this reservoir itself is pretty big enough to suffice a town. It is about 23 feet deep. The reservoir has 32 equal steps made of stone leading down to the bottom on both the sides. Many reservoirs like this one also had a well integrated within them, thus recharging the water table below the ground and assuring water supply round the year. In many cases reservoirs would recharge wells in the town. One quite intriguing fact is that the well is still filled with fresh water even after the passage of five millennia, especially in any area where salinity is in abundance.

We as professionals in water industry have to agree to one fact that collection of water is not as important as the distribution. Needless to mention, that in the year 2600 BC no piping material was known, probably, the only known metal was copper, which was not used to make pipes. Numerous and huge rain water drains have been unearthed at the site of Dholavira since 1989. And on the contrary to what was initially believed by the Archeological Survey of India, these drains were not used for draining utilities but for supplying and transporting water from one utility to another. The design of these drains was so unpretentious, that one could even easily walk into these drains using steps to clean or maintain them. The images below show some of such drains.

These drain ultimately connected to tenements / public baths where they would supply water for daily use. Considering the geographic location of Dholavira, summers would be scorching and would definitely bring in scarcity of water. Smaller reservoirs were also built within the township which were connected to these drains and would be supplied water. Also as mentioned many of the reservoirs had wells integrated into them which would be recharged and be readily available for use in the summer months. These wells and tanks were connected such to the supply drains that water could be easily diverted from these to the drains and the supply network would start functioning. In the adjoining image you can see the drain connected to the well.

The ruler of Dholavira also enjoyed benefits of the water supply system, but at a more luxurious level. What is supposed to be a swimming pool has been unearthed as well in the citadel region. Though what is seen presently looks like a new swimming pool superimposed over an old one. But who doesn’t like to play with water?

Of all the rain that was collected in the reservoirs further surface rainwater was collected and diverted to the collection reservoirs and tanks, another striking example of efficient rainwater harvesting. The adjoining image shows a collection pit and connection to a drain, worth noticing is how the area is sloped to achieve maximum catchment. Thus advanced were the Dholavirans, in what we call the stone age or dark ages. So what happened to them? By the end of 1750 BC there was nothing left of Dholavira except the ruins that are seen today. Three possibilities have come to light as to the sudden fall of this once prosperous town.

ndeed it is a matter of pride for us, that we Indians were experts in water distribution and management even in the ages when the western world was probably living savage lives.